When I shared with all of you recently that I’m working on a book for publication in 2027, I told you I was going to pull back on longer Sunday posts for awhile and instead share a few different types of short features, one of which I would title Bluelines. My idea was for “Bluelines” to be the label (like “This Week, I’m Reading…”) for posts that peek behind the curtain of how publishing works—but I never explained the back story of that title.

If you’re a former editor, too, this may be a fun dose of nostalgia because bluelines are one of those staples of old-school publishing that you never see today. I ran across them often early in my career, when I was working for a couple of different colleges in their publications departments and, even earlier, on an internship with British Heritage magazine.

Bluelines are the copy editing proofs an editor gets before a book, magazine, or publication goes, literally, to press. They’re like cousins of blueprints (is that term still used in architecture?) except that the background of blueprints was blue, and publishing bluelines were printed on white paper, while the lettering came out blue. I’m not going to pretend to understand the science behind them—you can read more about it here—but I do know that bluelines were part of a photochemical process, and they were made using the actual plates that were going to be used for printing. They were the very last proofreading step before the final product.

The final page proofs of my novel, which came out in 2012, came to me as PDFs printed on plain white paper, which felt oddly disappointing. The technology had obviously changed by then, but I realized that marking up a blueline signified something special for me, and I kind of wished I’d been able to do that for my own book.

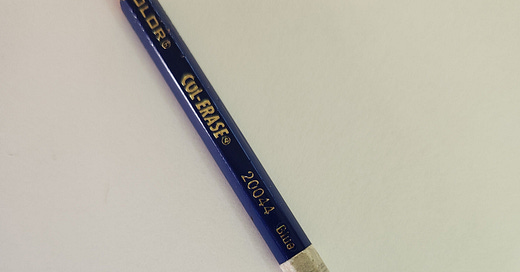

What Simon & Schuster did send me—and very specifically told me I must use—was a special blue pencil for marking up the PDF. I had to wonder: In the switch to PDFs printed in black ink, had some old-timer insisted on a blue pencil?

A blue pencil is not useful for much, and so, having been used for its task, it still stands in the pencil holder on my desk. For a long time, it was a reminder of the fact that I had failed to follow up that novel with another. But for some reason, I never threw it away. It doesn’t evoke good luck for me, and I’ll probably never use it again. But it does, in a funny little way, signal resilience and perseverance. So, I keep it there.

And that, my friends, is the story of bluelines. In future Bluelines posts, I’ll share some more stories about the publishing process. And if you’re curious to read more, here’s a great thread from some folks who worked with bluelines “back in the day.”

I am just as old—or older! The tools I used on a daily basis are antique artifacts now—ruling pens, rubber cement, white-out, Xacto knives, rubylith, stat cameras, etc. Actually they all sound kinda pretty—maybe a poem!