One of my favorite books about reading is Harold Bloom’s How to Read and Why. Bloom, who died in 2019, was one of the most brilliant literary critics of our time and a legendary professor at Yale. An acquaintance who was Bloom’s neighbor here in New Haven reported that he read so fast that he slowly turned the pages without pausing—and remembered everything. (The same acquaintance recalled how it felt to be home with young children reading Everyone Poops out loud while Harold Bloom was next door cogitating brilliantly about Shakespeare, although Bloom was apparently a lovely neighbor who, she conceded, probably would have had something interesting to say about Everyone Poops, too. But I digress.)

How to Read and Why—with the emphasis on the “why”—offers up miniature demonstrations of how to read a smorgasbord of selections from classic literature in multiple genres. The “how” essentially boils down to Bloom sharing what he finds moving and making connections among works of literature, which is an implicit argument that you should set aside historical context and rules about form (who cares how many lines a sonnet requires?), pay attention to what gives you insight into your own experience of life, and read a lot so you can find the interesting patterns and interconnections among the works you read.

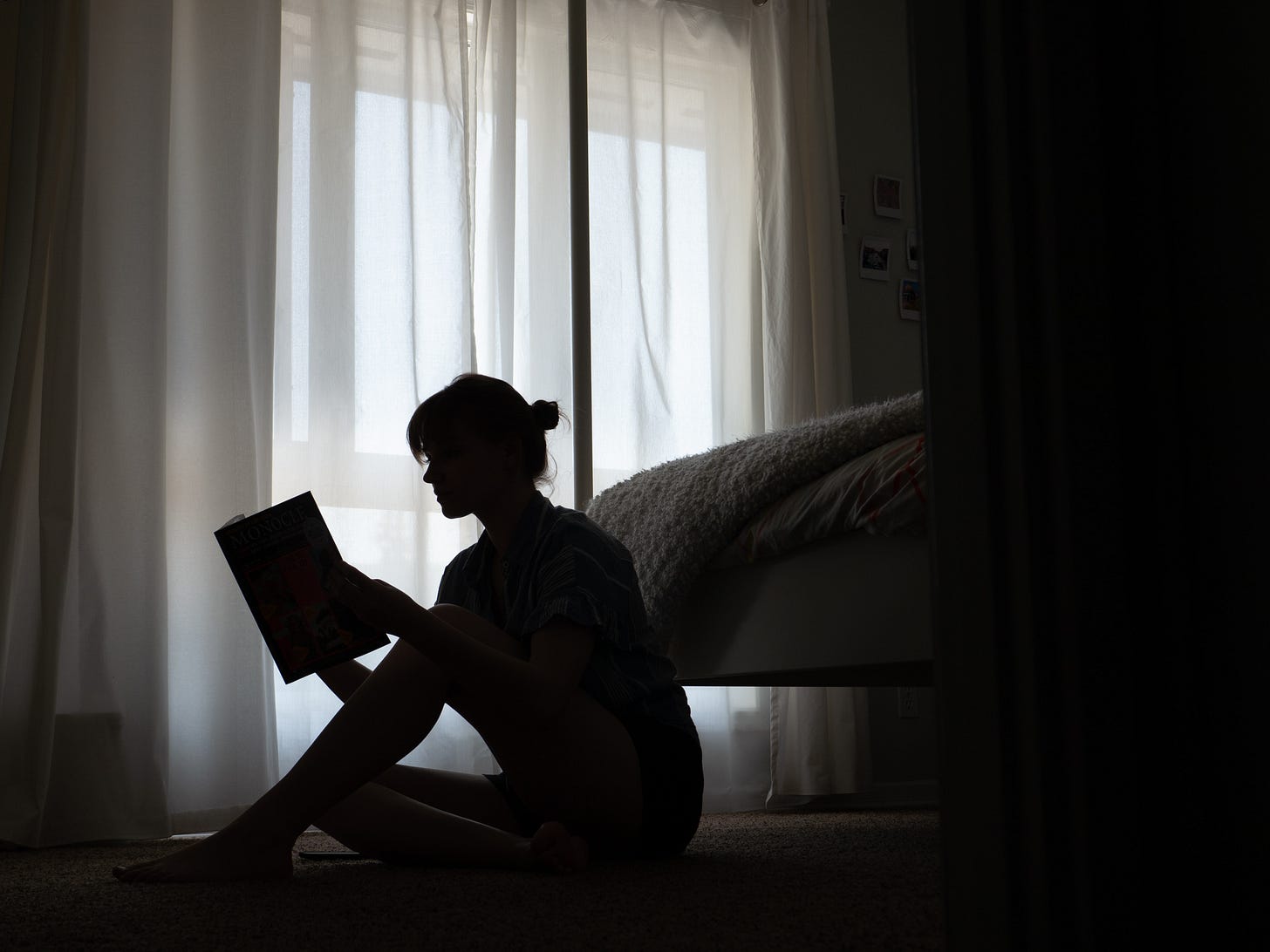

But what I actually like about this book is its preface and prologue, in which Bloom talks about reading as a solitary act. I’ve been thinking about that this week because many of us belong to book clubs of one stripe or another, and reading, for us, is often a social act.

So, what does it mean to be a solitary reader? Well, according to Bloom, that’s when we really tap into the deepest pleasures of reading, not in conversation with others about what we’ve read and certainly not in a directed classroom discussion. Bloom writes,

Ultimately we read… in order to strengthen the self, and to learn its authentic interests.

At the same time, reading is one of the best ways to spend your time alone:

Reading well is one of the great pleasures that solitude can afford you, because it is, at least in my experience, the most healing of pleasures. It returns you to otherness, whether in yourself or in friends, or in those who may become friends.

“Reading well,” Bloom says, gets you outside of yourself and immerses you in an imaginative world. We’ve probably all had that experience of entering the world of the book we’re reading. A few weeks ago, I wrote about “comfort books,” and that’s surely a big part of what makes them comforting—inhabiting them gives us a sense of belonging.

You may have noted that Bloom refers to reading “well,” and that’s the part that can strike insecurity like a stake through our hearts. At least, I’ve heard that from many readers who think they may not be “good enough” to have a conversation with another group of readers, so they’d just as soon stay home. Bloom wouldn’t argue with staying home, but his definition of reading “well” has nothing to do with being able to throw around big academic terms or make a good impression in your book club discussion. In fact, despite the fact that he’s an academic literary critic himself, he’s aware that the kind of reading we do in groups is a “performance”—it’s impersonal, often ideological, and sometimes even antagonistic.

In order to read well, he says (“fusing” the advice of three great thinkers to come before him), you must

find what comes near to you that can be put to the use of weighing and considering, and that addresses you as though you share the one nature, free of time’s tyranny.

To paraphrase (further), find something worth reading that will make you think about life’s big questions and who you are, something that “speaks” to you, and don’t worry about how long it will take or how many other books you want to read or how short your time is. Just read.

Bloom actually offers five principles for “reading well,” which is way too many to go into here, even though he himself delivers them all handily in eight and a half pages. I want to give you just one, and if you’re personally moved to find this book and read some more Harold Bloom, have at it. But if you simply want to think about what it means to “read well,” he offers this: “One must be an inventor to read well.”

What I think he’s suggesting you invent through reading is, essentially, your sense of self. In order to become an “inventor,” you need to trust yourself, and the only way you can learn to trust yourself as a reader is to read a lot—and read a lot by writers who also trust themselves, not writers who are following formulas in order to sell books. I mean, feel free to read those, too, but they aren’t going to disrupt the status quo in any way, which makes it difficult for them to show you anything you haven’t seen before.

For Bloom, the best first way to become a reader who reads well is to read Shakespeare; he essentially spent his career making that argument. I, too, love Shakespeare, but one limitation of this book is that Bloom is an old-school western canon kind of guy. Very few women and writers of color make their way into his work, which may say more about the canon than about Bloom himself. The books (plays, stories, poems, etc.) that give him the most may not be the books that give the most to you. Certainly, his favorite reads are not all my favorites. Halfway through Don Quixote, I was getting tired of hanging out with what is essentially a pair of early 17th-century bros and put the book down, unfinished. So, when Bloom tells me that “reading Don Quixote is an endless pleasure,” I figure that’s because it’s a buddy book, and I see why he likes it, but it doesn’t do as much for me. Ironically (or not), I have taken Bloom’s advice and become an autonomous reader who doesn’t need to agree with him on every point to appreciate him.

There’s a whole other essay bubbling at the edges of my thoughts about the western canon here, so I’ll put a lid on it for now (or, to make the metaphor work, take the lid off so it won’t boil over!). Suffice it to say that the works Bloom discusses in How to Read and Why “should not be interpreted as an exclusive list of what to read but rather as a sampling of works that best illustrate why to read,” as he explains. In any case, the principles of Bloom’s theory hold. Here’s a takeaway from the final paragraph of his prologue:

We read deeply for varied reasons, most of them familiar: that we cannot know enough people profoundly enough; that we need to know ourselves better; that we require knowledge, not just of self and others, but of the way things are. Yet the strongest, most authentic motive for deep reading of the now much abused traditional canon is the search for a difficult pleasure.

That oxymoron—“difficult pleasure”—may be hard to wrap your mind around until you’re presented with the only other thing besides reading deeply that will bring you to what Bloom calls “secular transcendence,” and that’s falling in love. If you’ve ever fallen in love, you can probably grasp what a “difficult pleasure” is.

So, “reading well” has to do with exposing yourself to the “difficult pleasure” of reading when it requires you to struggle a bit with its ideas, its structure, its diction—and to do so on your own. Some people are fortunate enough to have a great teacher to help them along the way, Bloom notes, but mostly the work is going to be yours. When you approach a reading, he says, “What matters most is who you are, since you cannot evade bringing yourself to the act of reading.”

I’m not sure where that leaves us and our book clubs. Obviously, they serve an important function or we wouldn’t keep reading and discussing together. Writing this post for you has actually given me the opportunity to think through that question more carefully. It’s interesting to think about how that “book club” experience differs from the kind of reading Bloom is talking about, and whether he’s right that we only experience the “transcendence” reading offers when we do it alone.

(photos by Gabrielle Dixon and rusyena, Unsplash.com)

Love this essay, Kathy! And I love that I now have permission to read alone!

I have read “How to Read and Why” and did not remember much other than the Shakespeare and that is was an overall “difficult pleasure”. Thank you for, with your excellent piece, reminding me why I looked to Bloom’s book in the first place.