Welcome to our first summer guest writer, Rita McCleary, on what she’s been reading this week! I’m still open to guest writers for this column on upcoming Wednesdays, so please reach out if you’re interested.

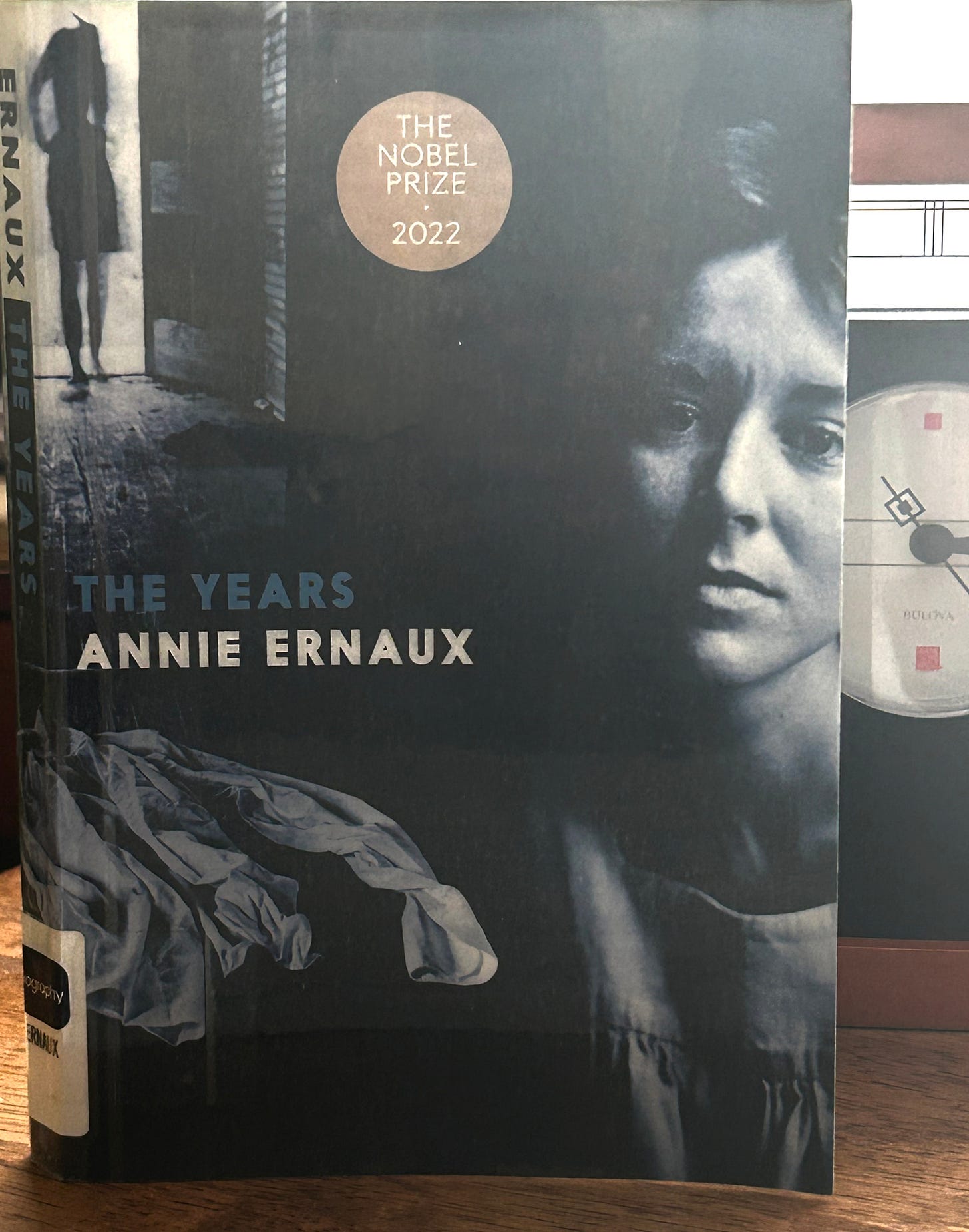

I finished reading The Years on Friday and felt compelled to go immediately back to the beginning. I felt amazed that I had forgotten that this odd and intriguing memoir has a prologue, that it does not begin with the detailed description of the sepia photograph of “a fat baby with a full, pouty lower lip,” dated 1941. I backtracked further to the epigraphs: “All we have is our history and it does not belong to us,” from José Ortega y Gasset, and a second, from Anton Chekov, that begins, “Yes, they’ll forget us. Such is our fate, there is no help for it.” Both the prologue and the epigraphs perfectly capture Annie Ernaux’s 2008 book, but in ways that I could not have anticipated when I began reading it. For more than half of it, I felt disoriented and distanced from her episodic and barely comprehensible narrative. I wanted Ernaux to tell me what she was getting at, and that required patience and imagination.

The Years is about the passage of time and the author’s fluid, even ephemeral and inevitably incomplete experiencing of her “self.” In fact, she only writes in the third person singular—“she”—as if observing, and in the first person plural—“we”—suggesting that she is not a singular individual, but a person whose living inextricably weaves in and out of constantly transforming relationships and events. If this sounds heady, it is. It is about how the discontinuities of what we do and do not remember become intrinsic to how we tell the tale of “our” lives. That I had to keep guessing for so long, I realized, was essential. Ernaux’s writing is immersive, not intellectual in any ordinary way. And for much of the memoir my feelings were more powerful than my understanding. Ernaux traces a chronology of her (our?) life, but with vignettes, impressions, and photographs. She evokes children at the dinner table listening to the grownups talk about The War and its ongoing deprivations; the strangeness of being both a book-smart girl and a girl whose sexual desires, deemed illicit by Catholicism, make thinking impossible; getting pregnant and getting married; feeling the energizing anger of May 1968, the conviction that protests would finally put an end to political oppression; then the growing despair that not much changes; then, eventually, indifference, and yes, some hopelessness. (I can especially relate to the hopelessness.) Even as “history” seems to repeat itself, though, to revert from change to status quo, Ernaux also conveys just how much has changed between her birth in 1940 and her concluding The Years in 2006.

So, how to convey who “she” is? Ernaux (third person singular) asks just this question on page 170 of a 230-page book: “She would like to assemble these multiple images of herself, separate and discordant, thread them together with the story of her existence, starting with her birth during World War II up until the present day.” And still it takes her another 20 years to figure out how to write this very book about “her”/“our” life, to create not an “explanation of self,” but to “go with herself only to retrieve the world, the memory and imagination of its bygone days . . . To hunt down sensations that are already there, as yet unnamed, such as the one that is making her write.”

What are you reading this week? Let us know in the comment section below!

Hi Diane, The Years was MY first encounter with Annie Ernaux, recommended to me by my adult son. From what (little) I’ve read about her, this memoir differs from others she’s written. In short: have at it! I’ll be returning the copy I checked out from Hamden Public Library tomorrow!

I'll put Ernaux on my reading list. Nice summary, Rita!

This week I'm reading Sense and Sensibility. I'm reading all of Austen this summer.